160 Years On, Our Founder’s Mission Still Stands Strong

Throughout 2026, the ASPCA will share highlights from our organization’s rich and sometimes unexpected 160-year history, including stories about our founder, Henry Bergh.

It’s not hard to imagine Henry Bergh, founder of The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, as a superhero of his day, a crusader for animal rights in Victorian-era Gotham City, determined to “prosecute those who persecuted poor dumb brutes.”

Though born into privilege, Bergh seemed more comfortable patrolling the grimy streets of 19th-century New York than basking in the luxury his wealth could provide.

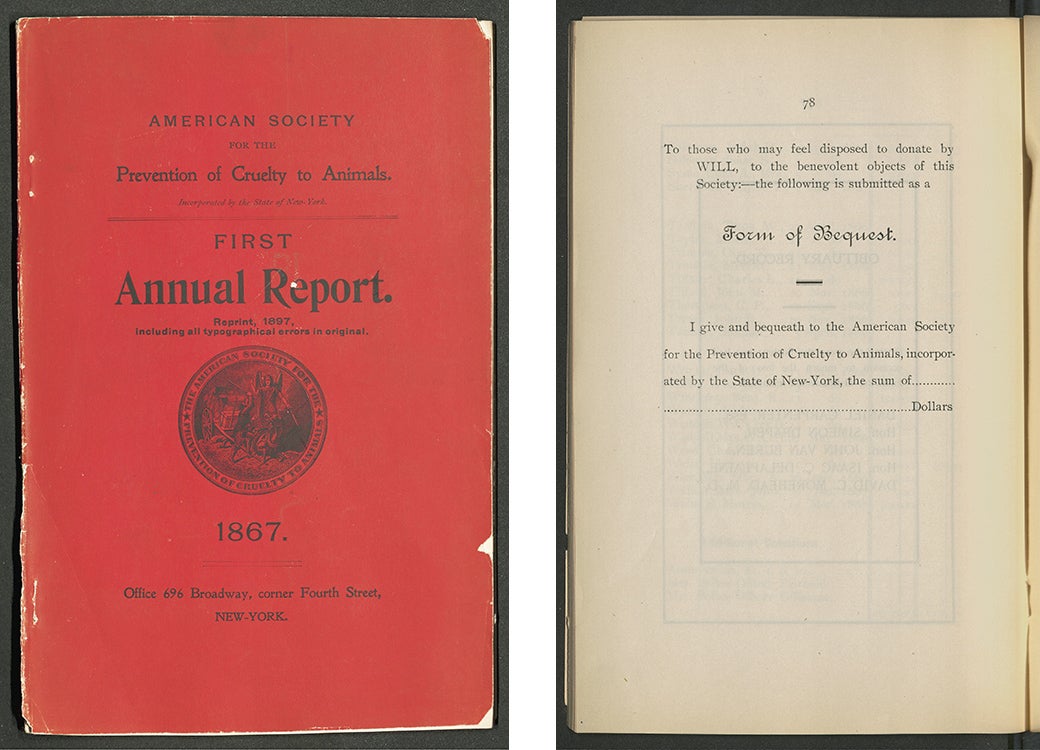

After founding the ASPCA on April 10, 1866, in New York City with the mission “To provide effective means for the prevention of cruelty to animals throughout the United States,” Bergh secured a written document, or charter, from the New York State Legislature that granted the ASPCA jurisdiction to enforce animal-protection laws throughout the state.

The law he drafted, “An act for the more effectual prevention of cruelty to animals,” was passed nine days after the ASPCA’s founding, making it a crime to “over-drive, over-load, torture, torment, deprive of necessary sustenance, or to be unnecessarily or cruelly beaten, or needlessly mutilated, or killed as aforesaid any living creature [...].”

The law also permitted the ASPCA to appoint its own agents: uniformed officers authorized to intervene on behalf of animals in crisis — a role Bergh often assumed personally. In its first year of existence, the ASPCA initiated 119 prosecutions and won 66 convictions.

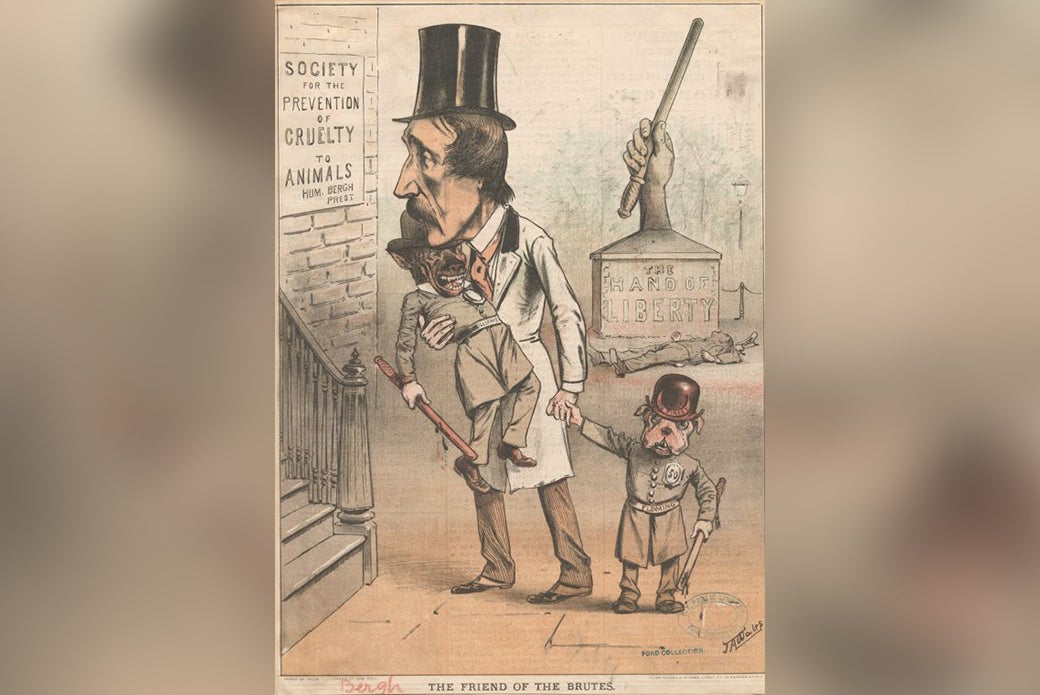

Bergh was often lampooned in the media as a busybody, dubbed “The Great Meddler,” among other names — a play on President Lincoln’s nickname, “The Great Emancipator” — due to his constant pursuit of perpetrators of animal cruelty.

- An early case had Bergh pursuing a butcher’s cart full of calves being transported to slaughter, stacked atop one another like firewood, legs bound. Bergh trailed the lumbering cart for many blocks and arrested the perpetrator, who was fined $10. The following day, he arrested three more men for similar offenses; each was fined $10 and spent a day in jail.

- In May 1866, Bergh went after the captain of a schooner that carried a shipment of turtles. Bergh discovered more than 100 tortured creatures below decks, flipped upside down, bound together with ropes pierced through their flippers and deprived of food and water. The captain’s lawyers argued the new law was not intended to include “lower” species such as turtles, then common table fare — even for Bergh. He lost the case, but public outcry and media attention bolstered his application of the law and drew supporters.

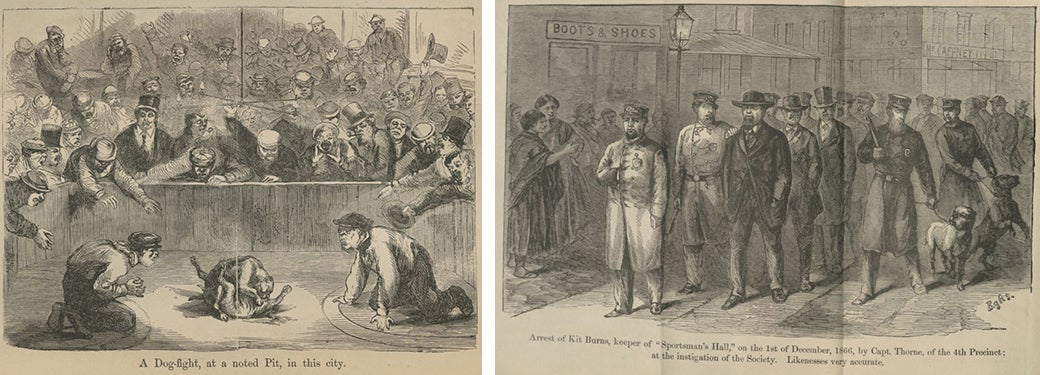

- Bergh relentlessly targeted the infamous dog fighter Kit Burns, once climbing to the roof of an arena to watch a dogfight through a skylight — a bout that ended with the arrest of Burns and a rival dog owner. Burns' final staged dogfight resulted in yet another arrest for him and many spectators.

Bergh knew his efforts would prompt ridicule, but he didn’t care. In fact, his dedication ran so deep that he hired a body double for mundane chores — like standing in for suit fittings — leaving him free to scour New York City’s streets, waterfronts, slaughterhouses and criminal underworld on a daily basis.

We know Bergh was distressed by the mistreatment of animals at least as far back as 1848, when he and his wife, Catherine Matilda, attended a bullfight in Seville, Spain. Sitting among 12,000 spectators, Bergh was appalled not only at the violent deaths of 16 bulls and 47 horses, but by the cheering and clapping of onlookers.

Fifteen years later, in 1863, the Lincoln Administration appointed Bergh to a diplomatic post in St. Petersburg, Russia. The 49-year-old Bergh possessed many appealing attributes — he was a well-traveled, well-respected, well-spoken aristocrat — that made him the perfect candidate.

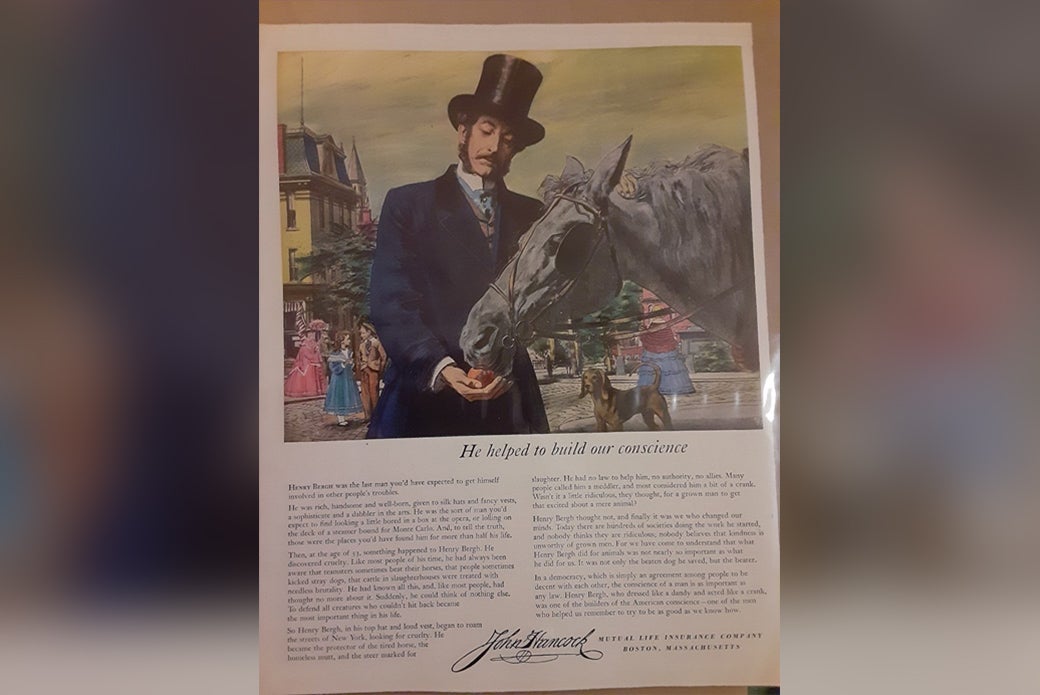

In St. Petersburg, Bergh witnessed the beating of a carriage horse and instructed his coachman to order the other driver to stop the abuse. Some accounts say that Bergh himself, his six-foot frame attired in a uniform of golden lace and signature stovepipe hat, stepped out of his carriage to berate the other coachman, who immediately put aside his stick and apologized. (Bergh would later do the same in New York City if he saw horses being overworked, as in the image below.)

Despite enjoying his post in Russia and aspiring to become a diplomatic minister, Bergh resigned within a year, returning to New York via London, where he visited and was inspired by the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (founded in 1824). He empathized with Richard Martin, an RSPCA founder credited with helping pass the first British law to protect animals from cruelty and who often took it upon himself to enforce it, as Bergh would later.

It's impossible to discuss Bergh without acknowledging the contradictions that shaped him. He had no pets of his own nor children to dote on, yet he created two organizations committed to their protection, the other being The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, founded in 1874.

Ultimately, in the tributes that followed Bergh’s death in 1888, he was memorialized as ahead of his time — guiding others toward kindness and mercy to animals.

In 1953, an advertisement for the life insurance company John Hancock Financial, above, depicted Bergh with reverence and respect while recognizing the ridicule he had endured in his lifetime. It reads:

“In a democracy ... the conscience of a man is as important as any law. Henry Bergh, who dressed like a dandy and acted like a crank, was one of the builders of the American conscience — one of the men who helped us remember to try to be as good as we know how.”

Many of the challenges the ASPCA faced in the 19th century persist in the 21st. Bergh’s vision — and the progress made over our 160-year history — continues to guide us today, shaping everything from investigations, legislation, law enforcement, behavior research and applications, fundraising, brand awareness, animal care and advocacy — the very pursuits that defined Bergh’s own efforts.